There were five pubs in town and one down by the river in the days when places to drink were very basic and drinking laws and customs were restrictive and, to say the least, bizarre. More on that later in this story.

This is not a large number of hotels for a town of this size, there were more in the old days. The Nepean Times reported in its issue of 30 September 1948 that in 1860 Penrith had eight hotels, as well as two banks, two schools and a couple of Masonic lodges. Must have been some heavy drinkers back then.

The pubs provided the only real accommodation in town. There were no accommodation-only hotels or motels in Penrith for a long while. Visitors to the town and travelling businesspeople had to stay in a pub or a boarding house. The hotel accommodation was generally room-only with a shared bathroom or two down the hall. No air-conditioning and the heating would have been electric radiators and hot water bottles.

The pubs had dining rooms to cater for their guests and these were also open to the public. Meals would have followed Australia’s dining habits at the time – soup, stews, meat with vegetables – beef or lamb (the price of poultry was prohibitive) – and unimaginative salads – ham salad, cheese salad, egg salad. And puddings, A pot of tea and slices of buttered bread were mandatory.

They also served traditional pub counter lunches rather than the trendy dishes served up today. A request for a roast pumpkin salad or buttermilk fried chicken would have been laughed at.

The hotels also did good business as a place for holding meetings. There were no convention centres or function rooms in the town other than a couple of rooms at the School of Arts in Castlereagh Street, or the Railway Institute near the station.

Most of the pubs advertised weekly in the Nepean Times and had their own little catchphrase, some of which in retrospect seem not only quaint but raise the question of why they needed to phrase it that way. It is surprising that the pubs advertised so regularly as nobody in the town would be ignorant of their existence and where they were, and they never had specials to advertise. Maybe the advertising was directed at out-of-towners.

The Top Pub (still there)

The Penrith Hotel in High Street, just down from Evan Street, popularly known as the Top Pub (top of High Street), was also known as Levy’s, after a previous owner. It was popular with police and the legal crowd, Both the police station and the courthouse (before it was rebuilt in Henry Street) were close by.

Teachers drank there too. If you walked past the pub after four o’clock and looked in the windows fronting the lounge, you could usually spot groups of teachers relaxing after a day at school. And who could blame them? They had little help from the Education Department and their only teaching aids were a blackboard and a piece of chalk.

Even after the courthouse moved, the hotel remained popular with the legal eagles, although it did lose some custom to the Australian Arms which was now closer to the courthouse than it had been.

One foolish licensee lost even more trade when Penrith’s hardest-drinking professional man, who had many hard-drinking mates, complained that he had been given change for a ten when he had handed over a twenty. Being drunk, he was probably wrong but instead of the licensee taking the long-term view of not offending a good customer, he refused the customer’s complaint. Result? The man and his mates never came to the Top Pub again. Revenue lost? Thousands.

In the fifties and early sixties, the host was Jock Bellis, a popular man and shrewd business operator who would never have made such a stupid mistake.

The advertising slogan for the Top Pub was ‘modern lounge and beer garden. Beer pulled under latest chilling conditions’.

The Arms (still there)

The Australian Arms was on the corner of Lawson Street which had been renamed from Castlereagh Street because it made no sense to Council to have the two arms of Castlereagh Street so separated.

The Arms was the pub of choice for bank and clerical workers as a lot of banks and offices were up that end of town. Tradies too enjoyed the beer garden at the Arms and the ease of parking in the side streets.

There was a big paddock between the Arms and Dr Uren’s surgery in High Street where carnivals and fetes were held. This provided added custom for the Arms.

The Arms’ advertising slogan? ‘A first-class dining room’.

The Federal (gone forever)

The Federal was on the north side of High Street between Woodriffe and Station Streets and its customers were the working men of Penrith. It closed in 1976 to the dismay of its many regular drinkers.

The Federal’s newspaper motto was ‘all liquor true to label’. Whether this was an apology for past transgressions or a dig at the other hotels, I do not know.

Tatts (still there)

Tattersall’s Hotel was on the corner of Station Street and High Street (south side) and is still around there. Its ads in the fifties boasted of ‘only the purest liquor sold, hot and cold water lock-up garages’.

Good to know that they had hot water for a bath but, like the Federal’s motto, the statement that only the purest liquor was sold is a bit of a puzzle. Perhaps the ad was suggesting that other Penrith hotels were in the liquor-diluting business. Who knows?

The CTA in the ad alongside presumably stands for the Commercial Travellers’ Association.

Tatts was a popular spot for meetings of sporting bodies. This may be because of its links with the famous footballer Dally Messenger. Apparently, Tatts was started by a relative, Charlie Messenger, in the late 1890s. It was named Tattersalls after the racehorse yards in England or possibly to give it some association with Tattersalls Club in Sydney.

Mrs Morrison was the licensee for many years.

The Red Cow (still there)

The Cow was and is a landmark in Penrith, as much for its name as anything else. In an era when pubs mostly had unimaginative names like The Royal Hotel, the Commercial Hotel and so on, the Cow had a descriptive name of the kind that you found in English pubs and the trendy drinking spots of today.

As I understood it, the Cow was built around the time that the railway came to Penrith sometime in the 1860s and was known variously as Smiths Hotel after the man who built it and the Railway Hotel – naturally. It had always had a beer garden. It was popular with railway workers and particularly train travellers, getting in a last one before going home.

The Cow’s ad told us that it had a sleeping out verandah and was sewered with electric lights throughout. It also boasted a cool beer house, whatever that meant.

The Cabin (gone and back again)

I loved the Log Cabin and had many pleasant Friday nights and Sunday afternoons there in the lounge, enjoying a live band or just the jukebox.

Situated as it was on the banks of the Nepean, it was a popular pub for both residents and tourists. It was always packed on GPS Regatta day.

Again, I understand there had been inns or hostelries in that general area since the early days of Penrith. The Cabin started out as a tea room called the Log House. The story is that it was built by a wealthy Sydney businessman who became irked when he could not get a decent cup of tea when travelling from Sydney to the Blue Mountains. It was later extended and became a licensed hotel with accommodation of a generally higher standard than available elsewhere.

Frank McKittrick bought the place in the fifties, upgraded it and added motel-type rooms but the pub was to all intents and purposes run by Miss McCredie, a tall and angular woman. If you were a really good customer and Miss McRedie liked you, she might let you doss down on a lounge in her office if you needed time to sober up before driving home.

The pub burned down in 2012. A great pity.

I understand that the Log Cabin has come back. That is good news but, for me, I doubt whether it will recapture those boozy Friday nights and Sunday arvos with our gang dancing to the jukebox in the lounge.

The bizarre drinking laws and customs way back when

Let’s start off with the customs. Until the liberation of the sixties, women were not allowed in the public or saloon bars of hotels and could only drink in the ladies’ lounge. Preferably not alone or too frequently to avoid getting a ‘reputation’. Popular drinks amongst women were shandies (beer and lemonade), brandy crustas, advocaat and cherry brandy cocktails (ugh!), and Pimms No 1 Cup.

Almost all pubs were ‘tied pubs’, that is they were either owned by one of the two breweries (Tooths and Tooheys) and leased out to the licensee or the licensee had an exclusive arrangement with one of the breweries. The consequence of this was that a tied pub sold only Tooths or Tooheys products and not both. If you were in a Tooths pub and wanted Tooheys New, bad luck. You would need to find a Toohey’s hotel.

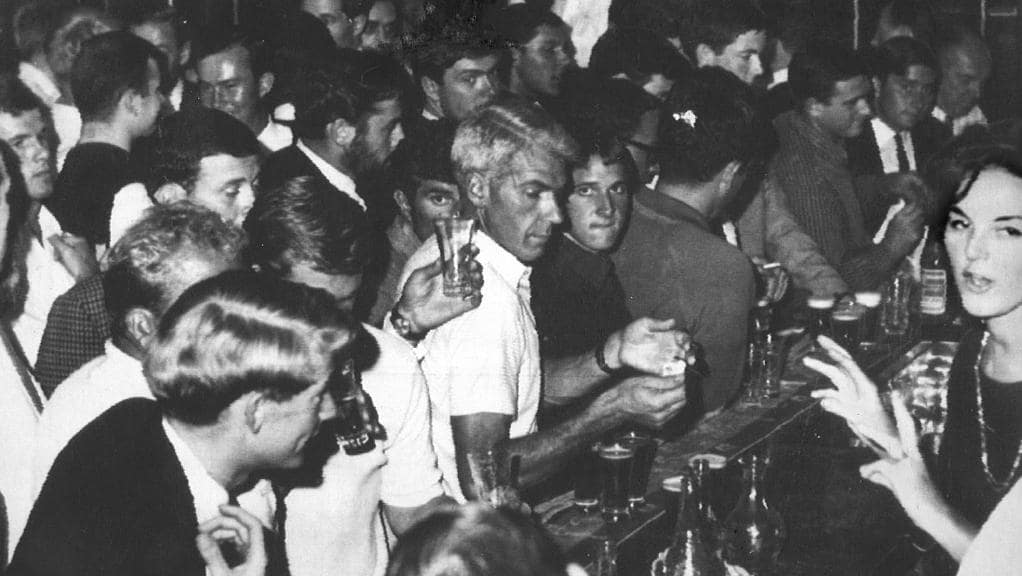

This monopolistic arrangement and the absence of women from the public bars of hotels meant that there was no real motivation to make the male drinking areas attractive – tiled floors, noise and a cloud of tobacco smoke made up the ambience. Frankly, the Ladies’ Parlours were not all that much better but they were generally carpeted.

Millers, a new brewery opened for business in, I think, the early sixties, built some hotels and made a genuine effort to make their bars presentable, if overly garish. A nauseatingly blue carpet and rotating chandeliers seemed to be standard.

This together, with the increasing admission of women into hitherto exclusive male drinking areas and the introduction of anti-monopoly laws, forced the existing pubs to lift their game in order to compete for customers and improve the appearance and environment of their bars.

The drinking laws and the six o’clock swill

Until 1955, pubs in New South Wales had to close at 6 pm. This led to the famous ‘six o’clock swill’ where drinkers tried to get as many drinks in before the pub closed. This was particularly inconvenient to Penrith people who worked in Sydney because by the time they finished work, there was little time to drink in a Sydney pub and by the time they got home to Penrith the hotels had closed. The Chips, for example, left Sydney at 5.24 pm and did not get to Penrith until after 6.

The laws were then liberalised and pubs were allowed to trade until 10 pm but to appease the temperance lobbyists there was a compulsory meal break between 6.30 pm and 7.30 pm during which time the pub had to close its doors. Although this made no logical sense, it meant that Penrith commuters could get a drink after they arrived at the Penrith train station, even if they had to wait a few minutes. It was not uncommon to see suited train travellers waiting outside the Red Cow for the doors to open at 7.30.

After several years, the compulsory meal break was abolished.

The nonsensical Sunday drinking restrictions

Even more absurd were the restrictions on drinking on Sundays. For some years, you could not buy a drink in a hotel on a Sunday unless you were a ‘bona fide traveller’. A bona fide traveller was someone who lived a certain distance from the hotel, I think 30 miles (50 kilometres).

So, even in a time when the dangers of driving after consuming alcohol were well known, the powers that be thought that it was okay to encourage people to get in a car, travel to a distant place, have a few drinks and drive back home.

Of course, the silliness of this law meant that nobody took any notice of it. Local residents would go to their local, sign the register that licensees were required to keep, give a friend or relative’s address outside the zone as their place of residence (or make one up) and then go in for a drink. It was pretty amusing to watch the local licensing sergeant walk into the lounge at the Log Cabin on a Sunday to check the register and greet drinkers by their first names.

Thankfully, this restriction too soon passed into history.

.

Pubs in the past

Penrith has been served by drinking establishments almost since its founding – inns, hotels, and sly grog joints. Lorna Parr of Penrith Council has written a really good story on these early drinking spots.

The Commercial Hotel

Riverside Inn

Today’s pubs

Penrith’s remaining pubs from those years – the Top Pub, the Arms, the Cow and Tatts -are now vastly different to what they were in the forties and fifties, external appearance aside. These hotels now are modern, well turned out, have a variety of entertainment and stock a range of beers that earlier drinkers could never have even dreamed of.

And – shock, horror! There are women in the bars.